Awake And Sing!

Written by Clifford Odets; Directed by Erwin Maas

Sea Dog Theater | 209 East 16th Street, New York, NY 10003

October 14 - November 8, 2025

Photo Credit: Jeremy Varner

In recent years, the theatrical landscape has been glutted with stripped-down, high-profile revivals—those star-spangled, coolly minimalist reinterpretations of the canon that fill Broadway houses with A-list actors and ironic austerity. Sam Gold, Ivo van Hove and Jamie Lloyd, those high priests of the bare stage, have made it almost fashionable to subtract rather than embellish. Yet Sea Dog Theater’s quietly incandescent Awake and Sing!—performed not in a cavernous commercial house but within the vaulted sanctuary of the Parish of Calvary-St. George’s—reminds us that genuine revelation doesn’t require a Broadway budget. It merely requires clarity, conviction, and a willingness to let the text breathe its own troubled air.

This should be obvious, and yet how often it isn’t. So many off-Broadway revivals of American classics cling to a kind of sepia-toned literalism, anxious to reconstruct bygone apartments with lovingly mismatched furniture and period wallpaper—nostalgia masquerading as fidelity. Clifford Odets’ 1935 family drama, a proletarian pressure cooker of the Depression era, usually falls prey to just such treatment. Conversely, a 2006 Lincoln Center Theater production presented on Broadway at the Belasco Theater directed by Bartlett Sher in a very traditional revival boasted a star-studded cast: Ben Gazzara as Jacob, Zoë Wanamaker as Bessie, Mark Ruffalo as Moe, Pablo Schreiber as Ralph, and Lauren Ambrose as Hennie. It went on to win the Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play. Catherine Zuber won the Tony Award for her costume design. But in director Erwin Maas’ hands, this Awake and Sing! awakens indeed—its rhetoric of struggle and suffocation newly amplified by a staging that trades realism for something altogether more poetic, more haunted, more daringly estranged.

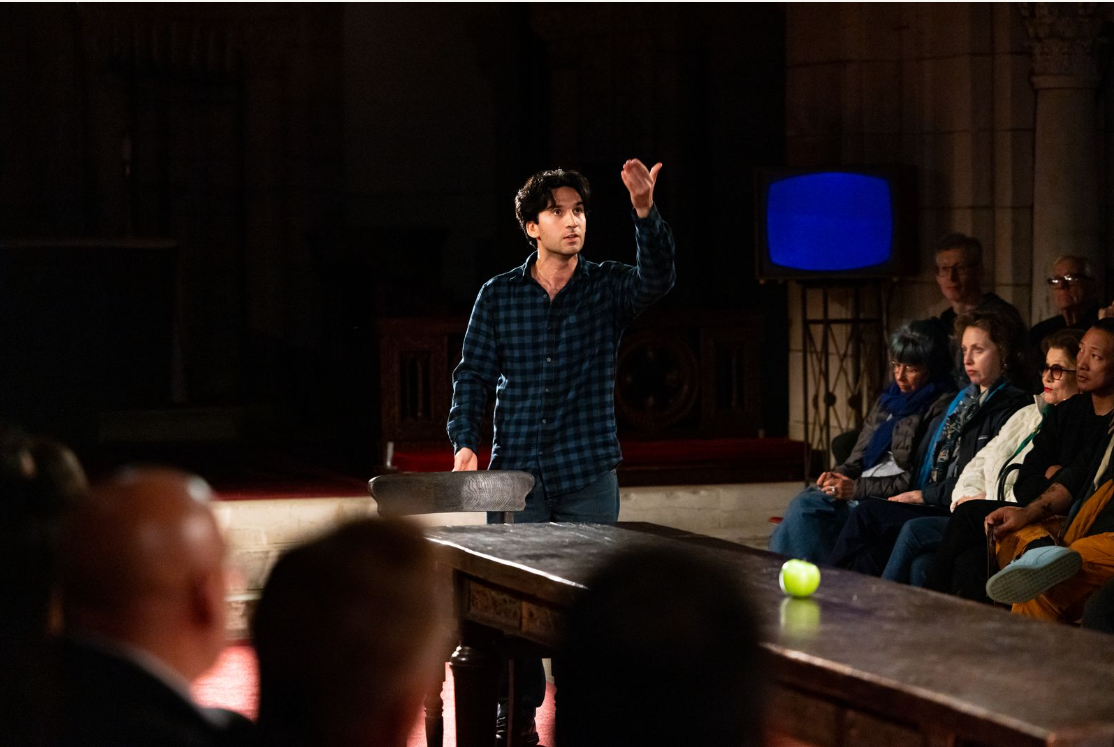

Ordinarily reserved for meetings and worship, this hallowed hall must be meticulously cleared and restored after each performance — a logistical burden that might daunt a lesser designer. Yet scenic designer Guy De Lancey transforms constraint into virtue, meeting the space’s transience with an ascetic ingenuity that borders on the sublime. Rather than attempt to domesticate the grandeur of the room, De Lancey embraces its sanctified austerity. The Berger family’s Bronx tenement apartment becomes, in Maas’ conception, a desolate expanse defined by a single impossibly long wooden table. The actors are marooned across it, often oceans apart, their shouted recriminations swallowed by the cavernous room. The audience flanks the action on both sides, invited to witness the family’s disintegration as though seated at a wake rather than at dinner. Props are forsaken, even a necessary telephone —save for a lone green apple, that cool orb of temptation and rot—while transitions are punctuated by eerie echoes, actor freezes and glacial blue light. At moments, actors vanish only to reappear on screens, their offstage reactions captured in ghostly close-up: the domestic sphere refracted through surveillance, memory, and regret. Fan Zhang’s atmospheric sound design and Hanxiao Zhang’s vibrant period costumes are faithful to Maas’ adherence to time and place.

To stage Odets’ Jewish Bronx family in the grand, Anglican vault of Calvary-St. George’s is to create a deliberate dissonance—one that Maas exploits to great effect. Stained-glass windows seem to shimmer with the ghosts of former congregations. The Bergers, dwarfed by ecclesiastical grandeur, are trapped beneath arches that mock their small domestic agonies. The setting lends their struggles a tragic, almost metaphysical scale: the banal horror of poverty elevated to the level of parable. The performance area, arranged in its runway configuration, becomes a kind of liturgical corridor — a place of ritual confrontation rather than illusionistic domesticity. The spareness is not a deficit but a statement.

If there is something Chekhovian in the family’s paralysis, Maas’s expressionistic flourishes tilt the production toward the existential; the air vibrates with the same anxious futility one might find in Sartre’s No Exit. Fear, failure, family—each an unseen warden of the soul. At the center of this suffocating tableau is Ralph (Trevor McGhie), the Bergers’ restless son, aching for a life beyond the long table. McGhie gives the role a bruised sweetness, his idealism perpetually colliding with exhaustion; by the play’s end, he seems prematurely aged, as if the air itself had eroded him. His nuanced portrayal is a performance that puts an actor on every casting agent’s radar. His tender scenes with Gary Sloan’s Jacob—the socialist grandfather whose convictions flicker like a dying candle—possess a rare intimacy, suggesting that Odets’ political compassion begins at the kitchen table, before it ever reaches the picket line.

As Bessie, the family’s iron-willed matriarch, Debra Walton is a study in controlled tyranny. Her voice cuts through the vaulted air with the assurance of a woman who long ago decided that sentiment is a luxury. By the time she erupts into her blistering final speech, we understand her not merely as an antagonist, but as the logical end point of a world that equates survival with domination. Daisy Wang’s Hennie, by contrast, floats through the play like a doomed wraith, her pregnancy predicament and loveless marriage rendered all the more pitiful by the staging’s frigid beauty.

Juan Carlos Diaz, ever an animated presence, lends to the weary Myron a haunting contradiction: a man whose physical restlessness masks the hollow ache of defeat. Diaz’s every gesture seems both eager and exhausted, as though he were performing the pantomime of vitality while his soul quietly implodes within. His Myron is less a patriarch than a ghost haunting his own household, radiating a melancholy that feels perilously close to recognition. By contrast, Alfred C. Kemp strides through the production with the easy confidence of a man accustomed to commanding rooms—and people. As Morty, Kemp’s beaming geniality conceals an undertow of threat; he glides from smooth-talking benefactor to quietly coercive power broker with chilling ease. His transformation is so fluid, so urbane, that one almost misses the moral rot beneath the polish—a regal predator cloaked in benevolence.

Sina Pooresmaeil—employing a textured Eastern European accent—brings to Sam a brooding tenderness that renders him both outsider and moral center. There’s an appealing awkwardness in his presence, a mixture of yearning and restraint, as though decency itself had been given a nervous human form. Pooresmaeil’s quiet intensity lingers long after he exits, the echo of a man who feels too much in a world that rewards those who feel nothing at all.

Not every risk pays off. The extreme minimalism sometimes muddies the narrative’s temporal shifts; the actors’ physical distance can often make the dialogue literally hard to hear. The overlong table certainly would be more at home in Macbeth’s castle as the scene-stealer at the banquet scene (Act 3, Scene 4), just waiting for Banquo’s ghost to pop out from beneath it. And Christopher J. Domig’s Moe, a war-scarred suitor consumed by bitterness, is played with such feral menace at times that Odets’ flickering sympathy for him all but vanishes. When he snarls about women “Take ’em all, cut ’em in little pieces like a herring in Greek salad,” we flinch—perhaps too much for the moment’s intended ambiguity. In the scene where Moe urges Hennie to run off with him, the audience becomes more aware of her abandoning her child than her finally getting the freedom she deserves. The television screens that perform surveillance duty are particularly hard to justify and are distractions even with nothing for us to view. Even if they were just televisions, most American families didn’t own one until the mid 1950s…a family in 1935, particularly one supporting three generations in a cramped Bronx tenement, would have been more preoccupied with putting food on the table.

Yet even when its directorial choices perplex, Maas’ Awake and Sing! remains gripping—an act of theatrical faith performed with monastic discipline and aesthetic courage. Sea Dog Theater has stripped away the play’s period trappings not to modernize it, but to expose the bones beneath: the fear, the yearning, the family that eats itself alive at the table of the American Dream.

Click HERE for tickets.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on October 27, 2025. All rights reserved.