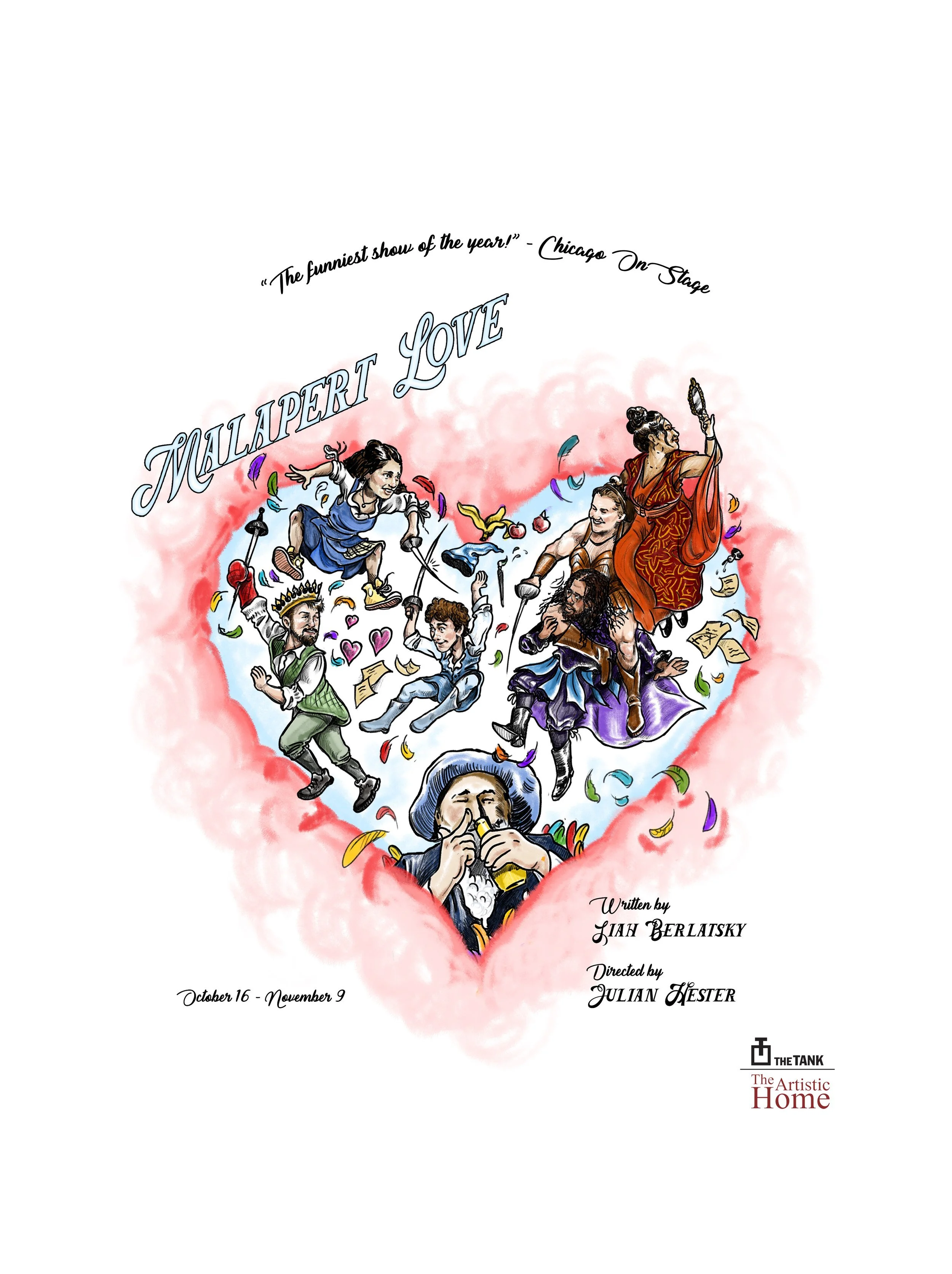

Malapert Love

Written by Siah Berlatsky; Directed by Julian Hester

The Tank | 312 West 36th Street, New York, NY 10018

October 16 - November 9, 2025

“Love,“ as Andy Williams once sang, is “A Many-Splendored Thing,” but then Pat Benatar sang “Love is a Battlefield,” so one of them is wrong…right? In Malapert Love, a joyous play from actor-director-turned-playwright Siah Berlatsky, idiocy becomes not merely a byproduct of affection but its very organizing principle. Berlatsky’s riotous, rapturous comedy—a heady blend of Shakespearean wordplay and Molièrian farce—unfolds in a cheerfully anachronistic Elizabethan Spain, where satin, satire, and sheer silliness reign supreme. Within Count Montoya’s castle, a giddy constellation of fools, lovers, and social climbers collide in pursuit of that most elusive of goals: romantic fulfillment. Naturally, they find instead a glorious mess.

The foppish Montoya—portrayed with breathtaking elasticity and wit by Grant Carriker—embodies that familiar comedic archetype: the nobleman too rich in leisure and too poor in sense. His latest folly is a passion for Gabriella, a neighboring gentlewoman of considerable spirit (and equally considerable vanity), whom he has never met but has idealized from afar. When his attempts at courtly verse collapse under their own purple weight, Montoya enlists his artistic servant, Skip, to tutor him in the language of love, first in a sonnet, then in a painting…a fatal decision, since the true poetry between them lies not in iambs but in glances. Declan Collins lends the role of Skip a beguiling mixture of grace, warmth, and understated wit. As the devoted servant whose heart betrays him, Collins exudes an effortless charm—his every gesture tinged with tenderness, his every glance suffused with quiet longing. In Collins’ hands, devotion becomes its own form of poetry: delicate, sincere, and utterly irresistible.

Berlatsky’s conceit—a “malapert” love, bold and improper across class boundaries—ripens into something both farcical and unexpectedly tender. The playwright toys with convention while taking it seriously enough to expose its absurdity. Every character is driven by the fever of misplaced desire: Esperanza (Emilie Rose Danno, a dynamo of comic invention) pines for the fool Molyneux (a wonderfully kinetic Ernest Henton), who in turn serves a master too enamored of his own reflection to notice the hearts breaking beneath his roof. Henton as Molyneux emerges as that most paradoxical of Shakespearean archetypes—the wise Fool, whose jests conceal philosophy and whose silences speak volumes. Far from being a mere purveyor of levity, he functions as the production’s moral barometer, a sardonic oracle cloaked in motley. He is less the jester at court than the conscience of the comedy—an ironic sage reminding us that folly, in the end, may be the only form of wisdom left to mortals. Petite in stature but titanic in comic presence, Danno delivers a performance of breathtaking bravura—a symphony of timing, precision, and audacious physical wit. Danno possesses that rare gift of the true clown—an ability to conjure laughter not by asking for it, but by inhabiting absurdity with absolute conviction. Fierce, fearless, and ferociously funny, she proves herself a comic force of formidable intelligence, shaping silence itself into a language of hilarity.

Meanwhile, Gabriella (a delightfully imperious Karla Corona) presides over her Amazonian attendant Lorca (the formidable Jenna Steege), whose swordsmanship and smoldering devotion lend the proceedings a pulse of earnest passion amidst the pandemonium. Corona proves herself a veritable rapier of repartee, slicing through the air with acerbic precision and gleaming wit. There is an almost musical sharpness to her speech—a percussive rhythm of disdain and delight—that transforms every exchange into a duel of intellect and attitude. With a single raised eyebrow or a languidly tossed insult, Corona asserts her dominion over the scene, a virtuoso of verbal combat whose every quip leaves her fellow players deliciously skewered. Steege seizes the evening’s spotlight with a performance of raw physicality and volcanic emotional charge. Her show-stopping soliloquy—delivered mid–musclebound posturing, each repetition a testament to both strength and self-mythologizing—transforms a feat of athleticism into an aria of embodied power. As she exalts her own virility, Steege fuses muscle and metaphor, sculpting a portrait of womanhood that is at once heroic, hilarious, and defiantly sensual. It is an explosive moment of theatrical alchemy, where form and feeling, sweat and poetry, converge in pure, triumphant spectacle.

Veteran actor and The Artistic Home’s longtime company stalwart Frank Nall brings his customary finesse to the role of Phischbreath, the production’s ragged yet oddly noble vagabond. Nall transforms what might, in lesser hands, have been a mere comic diversion into something far subtler—a study in droll restraint. With the precision of a seasoned craftsman, he wields deadpan understatement as both shield and sword, carving humor not from exaggeration but from the quiet absurdity of his own composure. His Phischbreath is a masterclass in controlled chaos: a streetwise philosopher cloaked in rags, radiating the sly wisdom of one who has seen too much and chooses, wryly, to laugh at it anyway.

Director Julian Hester marshals this mayhem with an expert hand, choreographing the production’s clockwork absurdity with precision worthy of Moliere. His command of rhythm and repose allows Berlatsky’s arch dialogue to bloom rather than blare. Each joke lands with the satisfaction of a perfectly aimed rapier thrust, while the physical comedy verges on the balletic. Hester has sculpted a production that is both disciplined and delirious—a rare feat in farce.

Kevin Hagan’s elegantly minimal set offers the cast a playground of suggestion rather than excess, its few movable pieces whisked across the stage by the actors, the all-purpose agents of chaos. A diaphanous canopy lends the room an ethereal, almost enchanted quality, a visual sigh that softens the play’s sharper edges with a hint of pastoral reverie. The balcony is an elegant feature, considering space in this particular Tank theater is in small supply. Complementing this vision are the handmade costumes by Mary Nora Wolf which deftly echo the sumptuous silhouettes of the Elizabethan period. Her designs marry historical suggestion with playful exaggeration—ruffles, bodices, and breeches rendered with just enough whimsy to remind us that this is less history than fantasy, a courtly dream refracted through the bright prism of comedy. Her costumes are a sumptuous parade of color and contradiction, while Petter Wahlback’s soundscape completes the sensory confection.

Yet it is Carriker’s Montoya who anchors this carnival of folly. His performance is a triumph of physical and linguistic dexterity: each contortion, each quip, each split-second shift between sincerity and self-parody testifies to a performer in complete communion with both text and tone. He recalls a true physical comedian, a young Bill Irwin by way of Cyrano, a clown-philosopher undone by his own desires.

Berlatsky’s effervescent script provides wit in abundance. Yet such excess feels almost integral to its charm. Like love itself, the play is too much—and thank heaven for it. Berlatsky is a playwright of rare linguistic agility and comic sensibility—a modern heir to the theatrical tricksters of centuries past. Under Hester’s inspired direction, Malapert Love emerges as both homage and invention, a dizzying fusion of Elizabethan romance and twenty-first-century audacity. One leaves The Tank not only laughing but strangely moved, reminded that the truest kind of foolishness—the kind that makes us human—is, indeed, being stupid together.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on November 10, 2025. All rights reserved.