Get Your Ass In The Water And Swim Like Me

Created by Eric Berryman and The Wooster Group; Directed By Kate Valk

Joe’s Pub | 425 Lafayette Street, NY, NY 10003

August 13 – 23, 2025

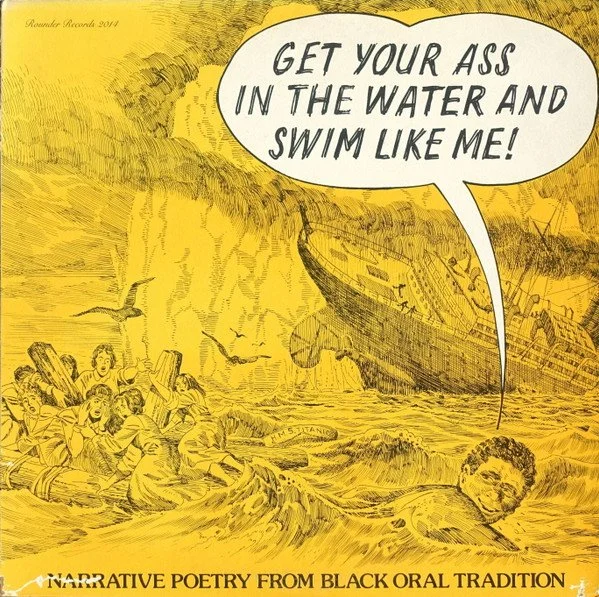

Based on the LP Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me: Narrative Poetry from Black Oral Tradition (Rounder Records 1976) recorded and edited by Bruce Jackson

If Eric Berryman is a vessel, then the show he stars in—and co-created with the ever-experimental Wooster Group, founded in 1975 —is the brew. Elizabeth LeCompte, a titan of avant-garde directing, still helms the company with unrelenting rigor. Yet in recent years, it is her longtime collaborator and performer Kate Valk who has begun to take the reins on select projects, bringing her own dexterous touch to the ensemble’s vision. Enter: Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me, a marvelously unexpected collaboration between Valk and the magnetic Berryman, an actor with the poise of a preacher and the mischief of a jester.

Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me is more than a revival or reinterpretation. It is an invocation, a summoning of ancestral voices, a love letter to a largely forgotten but deeply influential art form: the "toast"—raucous, rhyming, defiant spoken-word epics passed around like contraband at Black barbershops, street corners, prison yards, and house parties. These toasts, sometimes referred to as “ballads”, with their bawdy wit and mythic swagger, served as foundational DNA for hip-hop long before the genre had a name.

The production is a conceptual cousin to The B-Side: Negro Folklore from Texas State Prisons, an earlier Wooster work likewise starring and conceived by Berryman. His creative partners, The Wooster Group, are fearless cartographers of the inner life and the outer fringe. Both works operate as acts of cultural translation—channeling historical audio archives into kinetic, multisensory stagecraft. Indeed, Berryman’s relationship with this material is not academic—it is devotional. Raised in Baltimore by his mother, he was drawn to performance early, nurtured in a home where jazz was gospel. He trained rigorously at the Baltimore School for the Arts and Carnegie Mellon, but it was his encounter with SITI Company and the mythic figure of John Henry that sparked a deeper inquiry into Black oral traditions. That inquiry led him to Bruce Jackson’s field recordings of Texas prison songs and to the Wooster Group’s own Early Shaker Spirituals, a revelatory piece in which archival recordings became living theater. Berryman saw in that work a creative path.

Set within the imagined confines of a nocturnal radio station, call letters whispered, static crackling, Berryman as both host and history-keeper guides us through a vibrant retelling of “toasts”: longform, rhyming monologues rooted in African American oral tradition. These are bawdy, braggadocious tales of anti-heroes and miscreants, rich in wit and ripe with profanity. Berryman performs them with surgical precision and guttural delight, slipping into each character like a seasoned impersonator at a midnight radio show. He’s “on air,” yet utterly present—teasing, testing, and toasting the audience in kind. The language is ribald, rhythmic, unapologetically raw—steeped in the vernacular and vitality of the streets that birthed them.

The evening kicks off with the epic, delightfully profane “Titanic,” and Berryman wastes no time asserting his bold tone. He recounts the tale of Shine — a Black stoker on the doomed ship who, after being ignored by white passengers and crew while warning of the imminent disaster, declares “Fuck y’all, I’m out,” dives overboard with his survival instinct blazing. As the ship sinks, white passengers beg for help. Shine, utterly unbothered, offers only one legendary rejoinder: “Get your ass in the water and swim like me.” Berryman’s delivery drips with musicality and defiance, as Shine swims past the pleading, past a lusty white woman, past a racist shark, and finally onto dry land — thumbing his nose at the hubris of whiteness and surviving not in spite of it, but because of it. He does this apparently with time to spare for a drink in Los Angeles before the ship has even fully gone under. The piece is part roast, part legend, all rhythm.

Each of the eight toasts presented over the course of the evening contains its own peculiar fire. As the evening unfolds, we meet a rogue’s gallery of vulgar tricksters and poetic antiheroes: the trash-talking “Signifying Monkey,” the titular primate who locks horns with a lion and an elephant in a battle of wits and dominance, echoing tales as old as Aesop and as current as any viral meme. His disgruntled cousin in “Partytime Monkey,” which finds the simian protagonist aggrieved at being excluded from a Juneteenth bash, morphs into a surrealist protest against erasure; “Pimpin’ Sam,” who walks a tightrope between entrepreneurial legend and unsavory icon; “Joe the Grinder and G.I. Joe” tells of a soldier’s return from WWII only to find betrayal waiting at home, while the absurdly endowed “Flicted Arm Pete” spins a lurid yarn of a fornication contest that escalates into farcical carnage.

It all culminates in the infamous “Stackolee” — the murderous, hypersexual outlaw who has been immortalized in countless versions by everyone from Mississippi John Hurt to Nick Cave. Here, Berryman doesn’t just recite “Stackolee” — he seems to inhabit him, vibrating with the character’s reckless power and mythic stature. It’s a tale of blood, pride, and power, but also of lineage — a reminder that the Black experience isn’t marginal to the American mythos, it is the American mythos.

One might think the subject matter—crude, crass, and often obscene—would elicit discomfort. But the sophistication of the production, its deliberate theatricality, rescues it from mere vulgarity. Throughout, Berryman mixes his commanding recitation with modern tools: synthesized beats and sound loops triggered from a laptop, urban video vignettes that flirt with the absurd, designed by Irfan Brkovic, Andrew Maillet and Yudam Hyung Seok Jeon, inviting us to embrace the surrealism of the spectacle. A sound design builds an aural landscape so immersive it borders on hypnotic, conjured in part by Eric Sluyter’s savvy engineering. The effect is one of layering — voice over beat over memory over projection — much like the toasts themselves, which are stacked with metaphor, swagger, violence, and survival. Marika Kent’s lighting, alternately smoky and seductive, reminds us that we are adults now, fully equipped to laugh at the things we once whispered behind closed doors.

In this feverish tapestry of oral tradition and cultural reckoning, Berryman steps into the space not simply as a performer, but as a conjurer — summoning spirits, histories, and archetypes with the deftness of a griot and the demeanor of a street poet. As he recites the series of toasts — bawdy, violent, mythic, and subversive — he punctuates his storytelling with bursts of projected imagery: everything from high-octane car chases to grainy archival footage, and even real-time live shots of himself. These visual flourishes act less as decoration than as rhythmic counterpoints, syncopating the performance like samples in a DJ set.

But this isn’t just a solo act. Berryman is flanked — and in many ways grounded — by drummer Jharis Yokley, a percussionist of dazzling subtlety and wit. Yokley’s flourishes, rolls, and sudden eruptions give the toasts their heartbeat. The two performers occasionally drift into improvised repartee, personalizing the evening and reaffirming the living nature of the oral tradition they’re animating. The delightfully charismatic Yokley, provides more than accompaniment — he becomes a co-conspirator in the excavation of identity. In one such exchange, Berryman asks Yokley about his least favorite city/gig and whether he was breastfed or formula! It’s a seemingly light detour, but like everything else in this performance, it folds back into the larger inquiry: Who are we? Who gets to tell our stories? Who’s in the room when we tell them? It is a moment emblematic of the entire endeavor.

There’s no getting around the raunch and the violence — these tales are soaked in both, as bullets fly, backsides are laid bare, and dignity is lost and reclaimed in equal measure. Yet beneath the ribald humor and cartoonish bloodshed lies a disquieting pulse. To witness these tales — many rooted in Black oral tradition but performed for an audience that is often predominantly white — is to sit in a kind of cultural tension. The characters may veer into grotesque stereotypes, yes, but Berryman is keenly aware of this, framing them not as relics of minstrelsy but as larger-than-life figures akin to Hercules or Odysseus — flawed, excessive, mythic. “A community creates the heroes that they need,” Berryman reminds us, threading classical allusion through the needle of cultural survival.

But make no mistake: this is not comedy without context. These “toasts” are no less than foundational texts. They are the DNA of stand-up, the ghost-ancestors of Richard Pryor, Redd Foxx, and Moms Mabley. Before they were jokes in nightclubs or tracks on party records, they were performances on porches, in juke joints, on street corners. The so-called “chitlin’ circuit” of Black entertainment—part vaudeville, part survival—is America’s first true national touring theater. Its legacy lives on not just in hip hop and comedy, but in every facet of American performance. And yes, even in the hallowed halls of experimental institutions like The Wooster Group.

Toasts, too, were recorded—passed from mouth to mouth, record needle to ear, often played late at night when the kids were asleep and the whiskey was pouring freely. But threaded through these mythic voices are Berryman’s own—recorded and refracted, personal and performative. Valk, ever the sculptor of found text and found truth, encouraged him to turn his ethnographic lens inward. In one scene, Berryman contemplates his name—“Eric”—with a vulnerable hilarity, recounting the adolescent awkwardness of growing up amid Halimahs and Kaseems. Why not live as “Ehryk”?...But the evening is not merely a museum of Black folklore; it is an exploration of Black selfhood — past, present, and personal. The disclosure is intimate, comic, and quietly profound. (There is, he concedes, a Gary in the family — none other than Grammy-winning jazz legend Gary Bartz — but the connection is offered almost as an afterthought, a sly wink rather than a brag.) Here is a performer not merely interpreting the past, but inviting it into his own present—and reshaping himself in the process. Berryman’s artistry is not mimicry; it is mediumship. He is the vessel through which the ghosts of forgotten poets speak, joke, swear, swagger, and, above all, live again.

Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me is no mere exercise in nostalgia. It is an exhumation and a celebration of storytelling itself—especially the kind passed from mouth to ear, from generation to generation, long before anyone thought to call it "literature." What emerges is not just a historical reenactment, but a pulsating, deeply contemporary act of cultural restoration. Get Your Ass in the Water insists that these stories — coarse, comic, and contradictory — are not relics to be preserved behind glass. They are living texts, shaped by performance and community, and they resonate deeply within the continuum of Black expression — from street corner to studio, from the oral tradition to digital culture.

In an era of fleeting content and filtered truths, Berryman dares to stand still, to listen closely, and to speak boldly. This is not folklore on display — it is folklore in motion, alive and defiant, slipping through the fingers of history only to punch through the present with all its swagger intact. What The Wooster Group continues to do so well—what Valk and Berryman prove again here—is excavate the past not with nostalgic reverence, but with experimental precision. They don’t simply preserve the archive. They remix it, reframe it, reanimate it. Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me transcends curation. This is resurrection. This is reclamation. This is theater that sings, slaps, and stomps.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on August 25, 2025. All rights reserved.