In Honor of Jean-Michel Basquiat

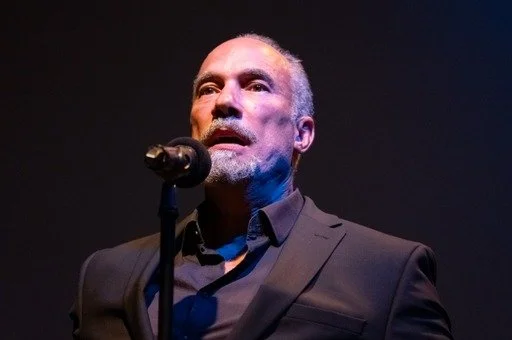

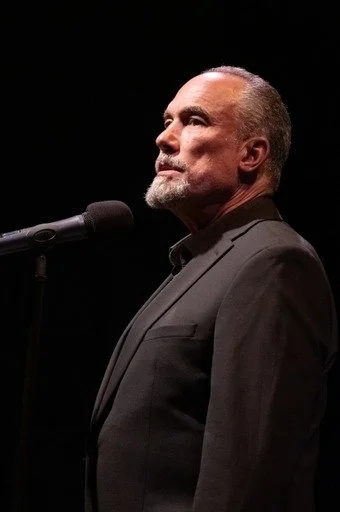

Written and performed by Roger Guenveur Smith

The Fourth Street Theatre at New York Theatre Workshop | 79 East 4th Street, New York, NY 10003

January 7, 2026 - January 18, 2026

Photos by Caroline Yang

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s life has by now hardened into a modern myth: meteoric, incandescent, and brutally brief. Son of a Nuyorican mother and a Haitian father, he burned through New York’s cultural firmament and, though born in 1960 he was dead by August of 1988, four months shy of his twenty-eighth birthday. In scarcely two decades of creative output, he produced an astonishing body of work—hundreds of paintings, innumerable drawings, and a set of collaborations with Andy Warhol that would permanently alter the vocabulary of late-twentieth-century art. Warhol, the most significant A-lister of downtown Manhattan’s avant-garde for three decades, presided over a porous, volatile ecosystem of artists, hustlers, poets, and dealers; mentored by Warhol, Basquiat moved through it like a charged particle, colliding with everyone. Among those collisions was a friendship with Roger Guenveur Smith—actor, playwright, director—who now brings his one-man meditation, In Honor of Jean-Michel Basquiat, to New York Theatre Workshop as part of the Under the Radar Festival for a two-week engagement.

Smith arrives at this subject with a formidable theatrical pedigree and a long-standing commitment to solo performance as a political and poetic instrument. Earlier works established a distinctive dramaturgical signature: rigorously researched, lyrically delivered, and unflinching in their engagement with American power, violence, and mythmaking. It is no surprise, then, that In Honor of Jean-Michel Basquiat continues in this vein—though here the blade is turned inward, toward memory, grief, and love.

Physically, Smith is almost austere, a man in a suit yet barefoot. For much of the nearly hour-long performance, he stands rooted to a single spot, as if pinned there by the gravity of memory. Movement comes not from locomotion but from modulation: a shift of the hips, a sweep of the arms, the reconfiguration of his face. These minimal gestures register with surprising force. The visual world around him is spare but eloquent. Arlo Sanders’ lighting design bathes the stage in shifting hues that gently transform the three-point crown Basquiat so often used to anoint his subjects as heroes. The crown hangs there like a benediction and a question mark.

This is not so much a play as it is a vigil. Smith does not dramatize Basquiat’s life in any conventional biographical sense; instead, he consecrates it. The text unfolds as a reverent meditation, edged with restrained fury, its emotional temperature carefully controlled. Central to the piece is the sound design by Marc Anthony Thompson, Smith’s longtime collaborator, whose sonic landscape functions as both historical context and emotional bloodstream. Jazz and blues, hip-hop and beatbox bleed into one another, threaded with the ambient noises of streets and weather, punctuated by tonal pulses that feel less like music than like the faint electrical activity of being alive. Within this soundscape, Smith releases facts and impressions in hushed, deliberate cadences, as if fearful that raising his voice might shatter something fragile and sacred.

Anger is in the room—how could it not be?—but it is never declaimed. Smith does not shout his outrage at the systemic injustices that circumscribed Basquiat’s life as a young Black man, nor at the cruel speed with which genius was consumed. Instead, the fury arrives obliquely: in the tightening of a phrase, the elongation of a pause, a glance lifted skyward that silently asks a question no theology can answer. The performance trusts the audience to feel the heat and the monumental grief beneath the surface.

What emerges is an intricate tapestry of events rather than a straight line. Smith traces the forces that shaped Basquiat with an almost astrological attentiveness. We hear of Basquiat’s father, marked by the terror of Duvalier’s Haiti, and how that inherited fear and discipline pressed upon his eldest surviving son. We hear of the childhood accident—Basquiat struck by a car at seven—and of the gift his mother brought to his hospital bed: Gray’s Anatomy, a book whose anatomical precision would later echo uncannily through his art. Smith recounts the years on the street, first as a runaway and then as a teenager driven from his home by his father for abandoning school, and the improbable ascent that followed: from graffiti and scavenged materials to the rarefied inner chambers of the art world, from poverty to earning more than a million dollars a year before he could legally rent a car.

Smith is particularly attentive to mirroring and recurrence. Throughout the piece, Smith draws parallels—events that align by age, by year, by emotional resonance—suggesting a universe structured less by chronology than by echo. At moments, he briefly inhabits other figures orbiting Basquiat’s legacy: the slick, self-satisfied auctioneer selling a painting for $110.5 million; a grieving woman kneeling at a cemetery, her private loss brushing against Smith’s own. Each vignette lands softly—small, contained, and yet carrying the full weight of joy and devastation.

Notably, the production resists the temptation to aestheticize Basquiat’s paintings themselves. Other than the one that greets us as we enter the theatre, Untitled (Crown) from 1982, there are no projections, no reproductions, no visual catalogue of crowns and skulls. We are told just enough: the graffiti origins, the spray paint and scavenged surfaces, the confrontations with racial, economic, and social hierarchies, the satirical barbs aimed at entrenched power. But the emphasis remains firmly on the man rather than the objects he left behind. The irony—one Basquiat himself recognized—is allowed to resonate without commentary: that the very elites he skewered would eventually pay obscene sums to possess his work, embalming rebellion in gold frames.

Smith’s relationship to Jean-Michel Basquiat is not a curatorial conceit or a retroactively claimed intimacy; it is lived history, forged in the charged social spaces where art and identity are tested in real time. Their first encounter took place not in a gallery or rehearsal room but on a dance floor in Los Angeles in the 1980s, that crucible of cultural crosscurrents where bodies, sound, and ambition collide. Basquiat arrived there as the newly incandescent prodigy from New York, already carrying the volatile aura of a talent moving faster than the systems attempting to contain it. Smith, meanwhile, was inhabiting a different but no less urgent creative identity: a Yale-educated writer and performer who had plunged headlong into Los Angeles’s politically inflected spoken-word and hip-hop underground, performing under the name “Hollywatts” with a ferocity sharpened by intellect and conviction.

What might have remained a fleeting, era-specific brush instead hardened into something more consequential. The friendship that took shape between them was animated by recognition—a mutual awareness of how art could function simultaneously as personal expression, political provocation, and cultural intervention. Their exchanges moved fluidly across disciplines and ideas, collapsing the artificial boundaries between visual art, language, rhythm, and resistance. In Smith’s telling, Basquiat was not simply an icon in the making but a fellow traveler in a broader struggle to articulate Black experience within—and against—the machinery of American culture. That early, chance meeting thus becomes emblematic: a moment when two distinct creative trajectories briefly aligned, generating a dialogue that would reverberate long after Basquiat’s voice was silenced, and that now finds renewed life onstage through Smith’s act of remembrance.

What is undeniable is the cumulative power of the evening: the elegance of Smith’s language, the discipline of his delivery, and the seamless fusion of tribute, gesture, and silence into a single, breathing organism. In Honor of Jean-Michel Basquiat does not seek to explain its subject so much as to sit with him—to honor a life lived at unbearable velocity and to translate that life into theatrical form. It is, in the end, a work of quiet magnitude, carrying a rare individual’s journey not through spectacle but through reverence, and lodging it gently, insistently, in the audience’s memory.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on January 18th, 2026. All rights reserved.