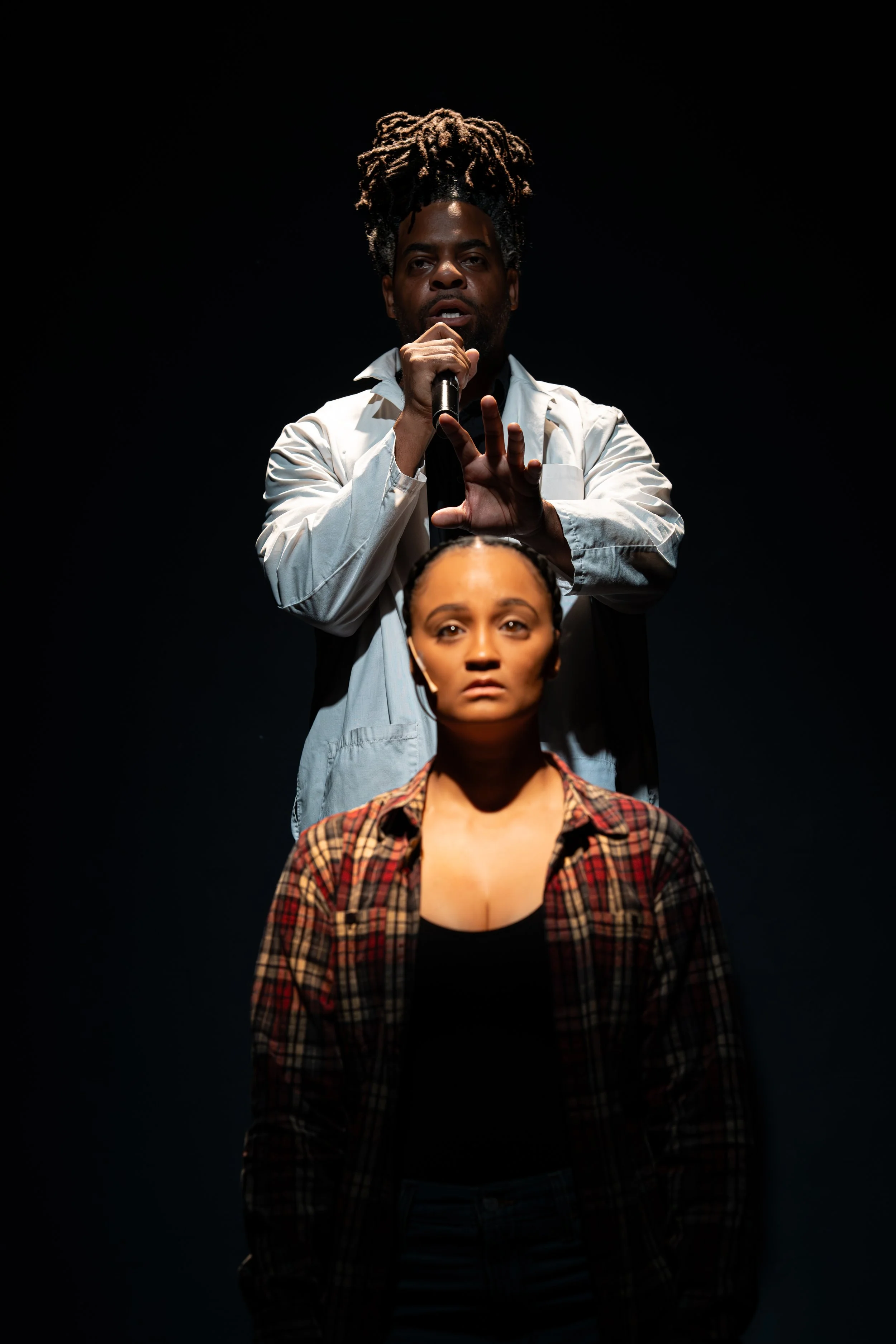

Dreamscape

Written and Directed by Rickerby Hinds

Andy Jordan Productions & Hindsight Productions present

Fringe Encores at 59E59 Theaters, 59 East 59th Street, Manhattan

January 7, 2026 - January 25, 2026

Photo Credit by Erin Lamar

A salutary interruption to the anesthetic pleasures that theatre so often provides, Dreamscape refuses the compact between stage and audience that promises escape. Instead, it insists on reckoning. In 1998, Tyisha Miller was shot and killed by police officers as she slept in her car, dreaming. Rickerby Hinds’ piece approaches that fact obliquely, poetically, with a restraint that paradoxically sharpens its force: Dreamscape is less a dramatization than a poem as autopsy, a careful examination of a future stolen before it had the chance to harden into memory.

The officer responsible for her death advanced a familiar and self-exculpatory narrative: that Miller had awakened, that she had reached for a weapon, and that his own actions were therefore a grim but necessary exercise in self-defense. It was a story rehearsed in the well-worn idiom of institutional absolution, one designed to transform a sleeping young woman into an imminent threat in the space of a sentence. Yet this account did not withstand scrutiny. In court, under the slow pressure of evidence and testimony, the claim unraveled, revealing itself not as fact but as fiction—a post hoc construction offered to rationalize an irrevocable act. The legal record would ultimately refute the officer’s version of events, but the damage of the assertion lingered, a reminder of how easily falsehood is mobilized to sanctify violence, and how rarely its collapse restores what has been taken. One leaves the theatre not soothed or satisfied but altered—carrying anger, grief, and, most insistently, a name that will not loosen its grip.

The production frames Miller’s life and death as a modern fable, one that demands repetition as an ethical act. Say her name. Say it again. The show situates us in the mutable terrain of dreams and inherited meanings—in the private cosmology of superstitions, wishes, and half-believed rituals passed from one generation to the next. Dreams here are not metaphors so much as sanctuaries: interior rooms where the self is briefly sovereign. Dreamscape asks what it means when even that final refuge is violated. What happens when the body opens its mouth to scream and nothing comes out—when judgment, sentencing, and execution collapse into a single, irreversible moment?

The figure at the center of the piece is Myeisha, a young Black woman from Southern California’s Inland Empire, rendered with specificity and affection. The work is steeped in a Black cultural vernacular that stretches from Los Angeles to any other city of Black injustice, from backyard barbecues to the low-grade millennial panic of Y2K. These references do more than set the scene; they thicken time, reminding us of the ordinary pleasures and anticipations that constitute a life. Myeisha never crosses into the new millennium; she never sees what the future might have made of her ambitions or her contradictions. We mourn her absence through the things she misses—cookouts not attended, blackouts not survived, debates not finished. Even the playful hypotheticals of adolescence—Denzel or Wesley, and in which scene from what film?—arrive freighted with sorrow, grounding us firmly in the nineteen-nineties while underscoring the story’s fatal immobility. Hip-hop and rap glide through the piece, touching on the frivolities of star signs and flirtation, all the while threading us toward an ending that cannot be revised. The effect confronts the relentless vulnerability of Black bodies and the grinding pursuit of justice that follows their destruction.

Natali Micciche’s performance is the production’s beating heart. She captivates the audience with an ease that never tips into complacency, shifting Myeisha from brash confidence to teasing humor to a final, devastating plea. Carrie Mykuls’ choreography gives Micciche a physical language that is both expressive and precise: she moves seamlessly from hip-hop swagger to cheerleader perkiness to the loose, joyful abandon of twerking, until the performance’s accumulating weight fractures that innocence. Micciche makes the stage her sovereign space entirely—yet the inescapable specter of the medical examination, of the forensic gaze that will soon reduce her body to evidence, hovers just beyond reach. The repeated counting of the bullets that pierced Tyisha Miller’s body—twelve, relentless and unforgiving—becomes a sonic and psychic trap from which neither performer nor audience can escape.

At one moment she leans toward us as if letting the audience in on a secret, trading conspiratorial anecdotes from her teenage years with the easy intimacy of someone assuming she is among friends; in the next, she is hurling verses sharpened by grief and lacquered with rage, language turned percussive, almost weaponized. The tonal shifts feel less like performance than survival, a young woman trying on different registers in order to be heard. When she pauses to ask, with a bitterness that lands somewhere between disbelief and indictment, “To protect and to serve, right?” The line arrives not as rhetoric but as citation. “It’s written there in black and white,” she adds, invoking the promise with a lawyerly precision that exposes its hollowness, the words suddenly estranged from the reality they are meant to guarantee.

Opposite Micciche, Josiah Alpher’s live beatboxing and sound design emerge as a work of astonishing subtlety. His vocal textures move fluidly from propulsive rhythms to the deadened monotone of a 911 operator, from lovingly sampled nineties medleys—Jodeci to Mary J. Blige—to a recurring tap-and-stutter motif that insinuates itself like a nervous tic. That sound becomes a cruel metronome, marking time as it runs out. Together, Micciche and Alpher generate a chemistry that holds the audience suspended between joy and dread, pleasure and foreknowledge.

Hinds’ direction and script demonstrate a disciplined understanding of tonal balance. Humor is allowed to bloom; charm is never withheld. But neither is permitted to anesthetize the violence at the work’s core. The coroner’s clinical reportage is staged with an almost unbearable clarity, laying bare the processes by which Black bodies are rendered objects—measured, catalogued, stripped of interiority. The audience is not invited to look away. Discomfort is the point.

In the end, Dreamscape functions as both memorial and provocation. It preserves the life of Tyisha Miller not by embalming it in sentimentality but by embedding it within the living culture from which it was torn. The show closes the way it began - Otis Redding provides the saddest rendition of “White Christmas” you will ever hear. The production does not offer closure. It offers continuity—the insistence that memory itself is a form of resistance, and that justice begins, however imperfectly, with attention paid to a beautiful life forever lost.

What emerges most forcefully is a bracing, almost accusatory reminder of what it means to be marked as other—not as an abstract sociological category, but as a lived, daily condition that seeps into posture, speech, and self-conception. The work insists that such treatment is never neutral, never merely symbolic; it exacts a toll that accrues over time, charging interest on every slight, exclusion, and misrecognition. To inhabit a life circumscribed by otherness, the piece suggests, is to pay continually for one’s existence, in vigilance, in compromise, in the quiet erosion of possibility. That this reminder arrives now only sharpens its resonance: the theater here becomes both mirror and ledger, reckoning with the costs we ask some bodies to bear so that others may remain comfortably unexamined.

Click here for tickets.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on January 18th, 2026. All rights reserved.