The Life and Death of King John

Written by William Shakespeare; Directed by John Gordon; Music Direction by Cam Gray

A.R.T./New York Theatres | 502 West 53rd Street, New York, NY 10019

August 27 - September 7, 2025

In Smoking Mirror Theatre’s clear-eyed, sharp-toothed, and slyly entertaining production of The Life and Death of King John, director John Gordon resuscitates this oft-dismissed political drama with such invigorating intelligence that one might be forgiven for wondering what generations of literary critics have been reading all these years. For here is a taut, acid-laced political thriller pulsing with power plays, ecclesiastical manipulation, dynastic desperation, and the kind of domestic betrayals that would make the Royal family blush.

Let us dispatch, once and for all, with the notion that King John is some feeble, shapeless cousin to Shakespeare’s more celebrated histories. In truth, it is a cold-eyed dissection of power and legitimacy, a study of the ways in which crowns are won, lost, and bartered like baubles at court. And far from being the eponymous hero, John—played with marvelous entitlement and jittery fragility by Bellamy Woodside Ridinger—is less a sovereign than a spoiled scion, a man-child thrust into rule and undone by every ounce of his inadequacy. Indeed, if the production has a thesis, it is this: that King John is a drama not about greatness, but the absence of it—and about those left to clean up the mess.

King John—the most reluctant of monarchs, the most irresolute of Shakespeare’s kings, is a sovereign in name, yet a cipher in action; a man possessed of ambition but bereft of conviction. In The Life and Death of King John, Shakespeare presents us with a protagonist whose character, such as it is, seems in a perpetual state of vacillation—an ever-fluctuating barometer of doubt, fear, and fragile ego. He is not the hero of his own narrative, nor is he a satisfying villain. He is, rather, the tragic embodiment of incapacity—a man who aspires to imperial grandeur but lacks the moral or strategic ballast to carry the weight of the crown he has inherited. He second-guesses nearly every move he makes: whether to wage war or sue for peace, whether to honor alliances or betray them, whether to execute a child or spare him. In one of the play’s most haunting arcs, he orders the death of young Arthur, his twelve-year-old rival and nephew, only to be seized by a queasy remorse that comes too late to stop the machinery he has set in motion.

Indeed, Shakespeare draws John as a man constantly reacting rather than ruling. He leans heavily—sometimes pathetically—on the counsel of others, most notably his imperious mother, Queen Eleanor, whose iron will is the only thing keeping his leadership afloat in the early acts. Without her, John flounders, drifting through a geopolitical maelstrom of shifting allegiances and ecclesiastical threats, incapable of asserting authority over either his enemies or his allies.

Enter the Bastard—a figure of far greater theatrical vitality than the king he serves. Philip Faulconbridge, the illegitimate son of Richard the Lionheart, emerges as a character of muscular clarity, moral skepticism, and salty patriotism. He functions not only as a military leader but as a sardonic chorus to the dynastic farce unfolding before him. And yet, for all his stage presence and pungent wit, he remains a commentator and a servant, not a player at the center of power. He may prod the king toward action, but he cannot eclipse the grim inertia that defines John’s reign.

It is in this disparity—the contrast between the Bastard’s vigorous plain-speaking and the king’s enervated dithering—that the play finds its central tension. King John is less a portrait of decisive leadership than a study in political impotence. The King of France, the Papal legate, Queen Eleanor, Constance, even the dead boy Arthur—all exert greater narrative force than John himself. He is a monarch buffeted by others’ wills, a man who sits upon the throne as if by accident and governs with the indecisiveness of one who knows it.

There is, of course, a tragic grandeur in this. John’s weakness is not simply personal; it is systemic. He is a ruler caught between eras—between the divine right of kings and the creeping influence of papal authority, between feudal loyalty and national identity. His failure is not Shakespeare’s mistake but his diagnosis. John is, ultimately, a ghost of greatness—haunted by the legacy of his brother Richard, undone by his own moral anemia, and destined to die not in triumph, nor in justified ruin, but in ignoble obscurity.

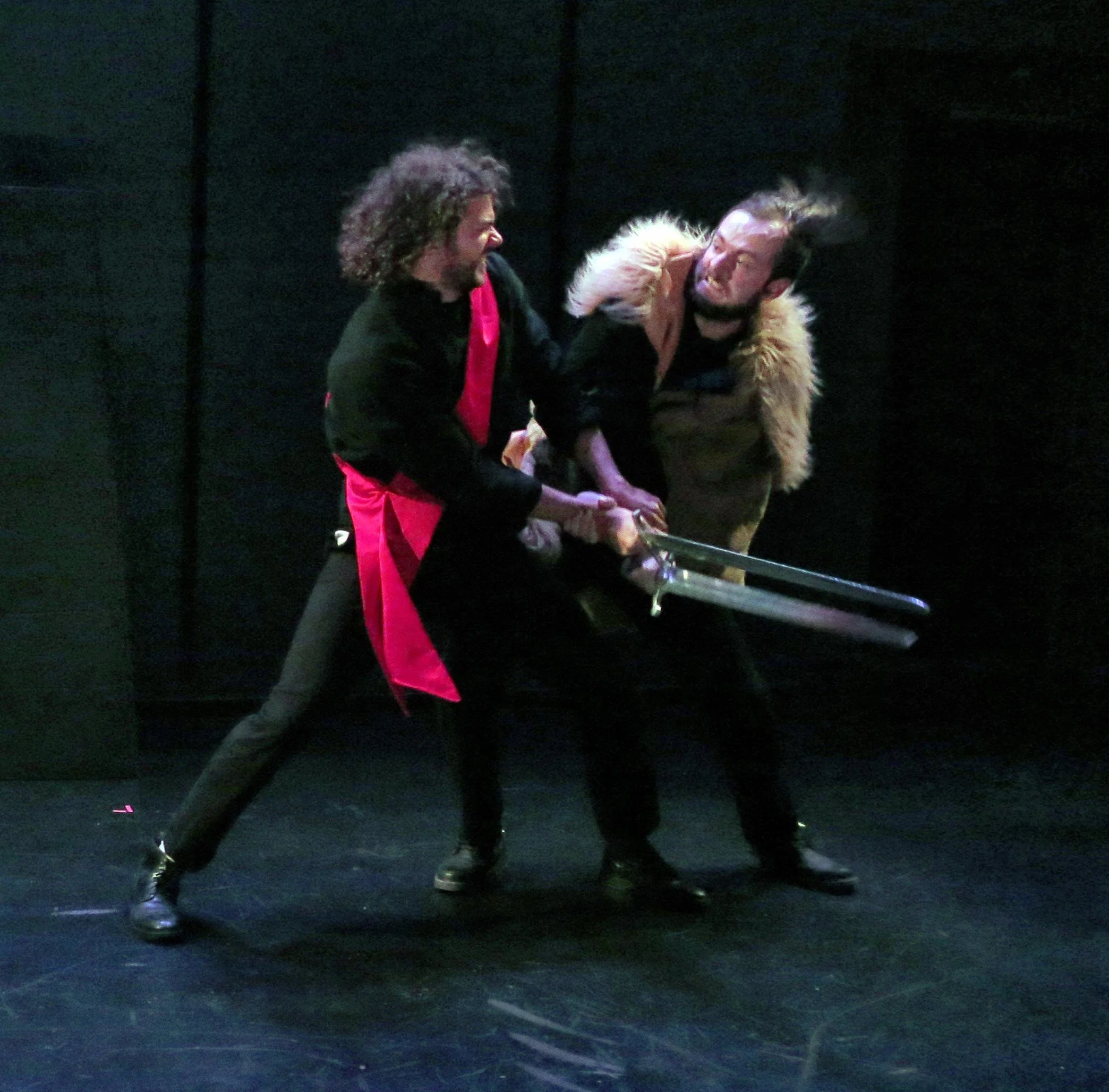

Director Gordon’s choice to set the entire affair in a mostly barren space of a section of castle wall and a throne—imagine Succession reimagined by Jerzy Grotowski Poor Theatre—proves astute. Gone are the dusty battlements and chainmail clichés. Instead, words become weapons, family meetings turn to war councils standing room only, and the fate of nations hangs in the air between Family Feud tableaux. If the concept strains credibility and an audience’s attention span at the margins, it nevertheless sharpens the play’s focus on dynastic drama as blood sport.

The cast is uniformly strong, but it is the women—those so often shunted to the side in Shakespeare’s histories—who emerge here as the prime architects of the play’s moral and emotional scaffolding. Victoria Hedgeberry’s Queen Eleanor exudes iron-willed pragmatism, a regal presence cloaked in stately weariness. She is the hand behind John’s rise, the only real monarch in the room, and her absence leaves a vacuum no man can fill. Opposite her, Ruby Rich’s’ volcanic Constance is a riveting portrait of maternal fury, unraveling with operatic force in pursuit of her son’s crown. When she demands “War! War! No peace!” it is less a political statement than an existential howl—a mother’s love curdled into obsession.

Her son, young Arthur, played with aching sincerity by Tessa Grace, is the closest the play comes to virtue—a gentle, unwilling pawn in this ruthless game. His quiet dignity and plaintive lines about shepherds and peace land like gut punches amidst the clamor of ambition. His death, rendered with shattering simplicity, serves as the moral hinge of the play: the innocent crushed beneath the gears of statecraft.

And yet, amidst this operatic tragedy, there is comic gold—bitter, earthy, and exquisitely played by Mateu Parellada as Philip Faulconbridge, the Bastard. This is Shakespeare’s first truly great outsider, a proto-Hal, part Falstaff, part political commentator, and Parellada imbues him with both roguish charm and unexpected gravitas. He is our surrogate, our snarky conscience, and by play’s end, he’s the only figure left standing with anything resembling integrity.

Fareeda Pasha as King Philip II of France provides the requisite statesman-like attributes that gives us what amounts to the antithesis of the lacking in kingly demeanor we see in John. Pasha makes the most of the moment where after the Cardinal has excommunicated John because of his opposition to the church, the French king must break his alliance with John and resume the battle between the two thrones.

Of course, no staging of King John can avoid the shadow of the Catholic Church, and here the production excels. Martin Challinor’s Cardinal Pandulph is the puppet master par excellence, delivered with chilling restraint and serpentine calculation. The Church, as embodied by him, is less spiritual beacon than power broker, ensuring that no crown sits comfortably atop any sovereign head. His manipulation of France and England into renewed conflict, just as peace seems possible, is Machiavellian theater at its finest.

In this ambitious staging, Challinor is entrusted with the formidable task of inhabiting not one, but two crucially divergent roles—an undertaking that demands both technical dexterity and emotional nuance. In addition to his primary portrayal, he dons the mantle of Hubert, the conflicted knight whose loyalty to King John is tested in the most harrowing of moral crucibles. It is Hubert, after all, to whom the monarch entrusts the chilling command: to rid the realm of the young Arthur, a deed that Hubert, to his credit—or perhaps to his torment—is ultimately unable to carry out. Challinor navigates this duality with remarkable finesse, delineating each character with clarity and purpose. What is perhaps most commendable, however, is his deft command of the play’s linguistic architecture. In a production where the demands of blank verse often prove too steep a climb for much of the ensemble, Challinor stands out as one of the rare few who not only comprehends the rhythm and weight of Shakespeare’s meter, but who also employs it in service of character and story. His articulation, grounded and resonant, lends the verse a muscularity and grace that elevate his performance and, indeed, the entire production.

We see only too vividly one does not leave King John admiring its titular character. One leaves marveling that Shakespeare, in his protean genius, could craft a history play in which the king is not the hero, not even the villain—but simply the void around which ambition, conscience, and chaos orbit. Smoking Mirror Theatre’s King John is not merely a reclamation project; it is a rebuke to centuries of critical myopia. It reveals a play that is not broken, but bristling with relevance—a story of mothers and fools, of pawns and kings, of fragile peace and the greedy hands that shatter it. One leaves the theater not bewildered by Shakespeare’s obscurity, but by the critical blindness that allowed it to languish so long in the margins. This is, without question, a King John to be reckoned with.

Click HERE for tickets.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on September 4, 2025. All rights reserved.