WE HAVE NO NEED OF OTHER WORLDS (WE NEED MIRRORS)

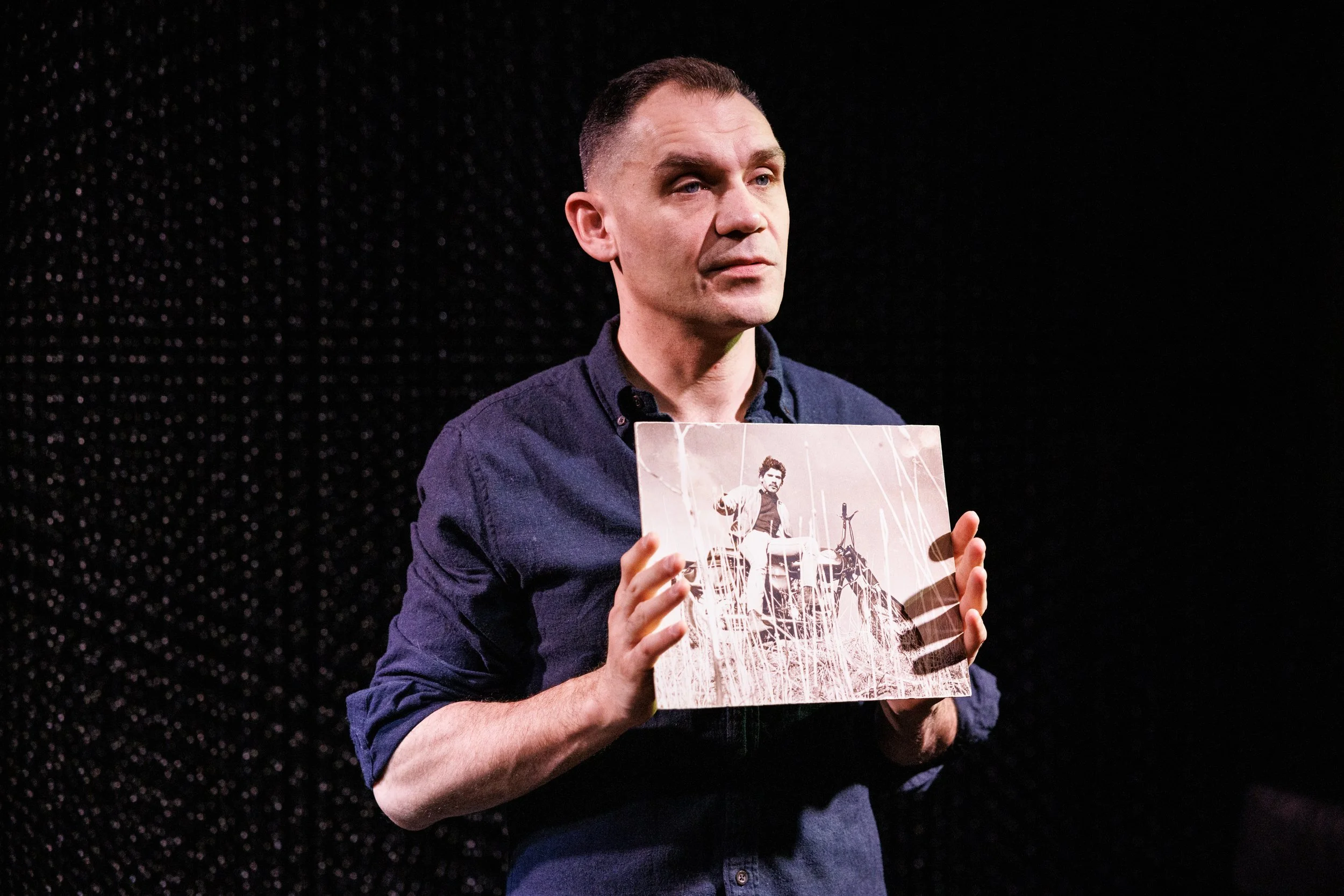

Created, Written and Performed by Graham Sack

Onassis ONX | 45 5th Ave, New York, NY 10022

January 9, 2026 - January 12, 2026

A son sits watch at his father’s bedside, performing that most ancient and helpless ritual: reading to the nearly departed in the hope that language might serve as a tether. The text he chooses is drawn from the father’s own journals—logbooks of a life spent traversing oceans and jungles, charting not only geography but metaphysical weather. These entries, dense with cosmic rumination, land on the ear with an uncanny chill. They seem less like records of what was than dispatches from what is happening now, as if the father, in some earlier, lucid season, had already glimpsed this dimly lit room and the figure of his son beside the bed. The production invites us to entertain a seductive metaphor: that the lesion blooming in the father’s brain may be misnamed as illness when it might equally be understood as aperture—a “wormhole” through which selves, eras, and possibilities leak into one another.

We Have No Need of Other Worlds (We Need Mirrors) takes this intimate vigil and dilates it into a hybrid theatrical environment where performance and immersive media blur into a single, porous membrane. The piece concerns itself with the triangulation of family, memory, and technology, but it resists tidy theses. Instead, it drifts—deliberately, hauntingly—through states of recall and projection. Interactive systems, live video, and an intricately sculpted soundscape bind audience and performers into a shared circuitry, so that spectators become less witnesses than participants in an unfolding transmission.

The result feels like an elegy refracted through a laboratory prism. At moments it resembles a “biometric séance”, with data standing in for ectoplasm and screens serving as spirit slates; it unfolds as a live theatrical and media encounter in which technology, sensation, and a strain of the spiritual intermingle, creating an experience that feels at once engineered and ineffable, as if circuitry and soul were briefly speaking the same language. A “digital phantasm”—part avatar, part cosmic glitch—flickers at the edges of the experience, suggesting a universe whose fabric is not fixed but glitching, receptive, alive. The work’s central provocation is both simple and vertiginous: that memory may not be a static archive stored in the brain but a signal in transit, moving across time like a radio wave, searching—patiently, desperately—for a receiver. In this schema, the theater itself becomes that receiver, a chamber where the past calls out and, for an hour or so, someone answers.

We Have No Need of Other Worlds (We Need Mirrors) arrives burdened with a title that sounds less like a marquee invitation than a graduate seminar thesis, yet the production it names is, in practice, a model of aesthetic clarity—cool, spare, and technologically lustrous. The mismatch is almost comic: a mouthful of metaphysics presiding over an experience that communicates most eloquently through light, space, and silence.

The provenance of the title explains some of its heft. It is borrowed from Stanisław Lem’s Solaris, that endlessly generative science-fiction novel (and cinematic muse) in which the cosmos functions as a hall of mirrors, returning to explorers not discovery but confrontation with their own psychic sediment. Lem’s idea—that our search for the alien often culminates in an encounter with the unresolved self—hovers meaningfully over Graham Sack’s project. Still, one senses that Sack, working with the technical collective LedPulse, has fashioned something sufficiently singular to merit a name unmoored from homage. This is not a footnote to Solaris but a live, flickering inquiry of its own.

The beating heart of the production is LedPulse’s DragonO Volumetric LED Display, a responsive sculptural grid that organizes thousands of points of light into a three-dimensional matrix. To step before it is to feel one has wandered inside a monumental Lite-Brite—an association that will tickle the nostalgia centers of anyone raised on the tactile technologies of the seventies and eighties. Yet DragonO is no toy. It “thinks,” in the limited but evocative sense that it registers and reacts, composing luminous architectures that feel less programmed than conjured.

Within this glowing lattice, Sack undertakes a personal excavation: the memory of his father’s final night, refracted through present-day recollection and a cache of journals dating back to 1967. The LEDs oscillate between figuration and abstraction. At times they sketch the recognizable contours of a hospital bed or the swell of ocean waves; at others they dissolve into visual metaphors for duration, grief, and departure. Time seems to pixelate. Emotion becomes geometry. The effect is frequently ravishing, as if memory itself had been given a dimmer switch and a third dimension.

What emerges is a work of genuine hypnotic power—meditative without becoming inert, intimate without lapsing into confession-for-its-own-sake. The sound design by Matt McCorkle deserves particular praise: it wraps Reza Behjat’s sensitive lighting in a sonic atmosphere that lends weight and breath to what might otherwise risk becoming pure spectacle. One feels the images resonate in the chest as much as in the eye.

For all its sensory sophistication, the piece wears its dramatic stakes with a kind of deliberate gentleness, trusting the audience to lean in and complete the circuitry. Sack’s recollections of his father are tender and finely grained, offered less as thesis than as invitation. The questions that surface—why return to these journals now, what present longing animates the search, how a son is subtly reshaped by such acts of remembrance—feel purposefully open, allowing the work to breathe in the mind long after the lights dim. Rather than spelling out a single trajectory, the production offers constellations of moments through which each spectator may trace a personal path.

Sack stages one of the most quietly devastating final images one is likely to encounter in the theater. When he learns that his father has died, the surrounding machinery of ordinary life resumes with almost cruel efficiency: relatives peel away toward breakfast, the day insisting on itself. Sack alone resists the forward pull of routine. “I’m not leaving,” he repeats, a refrain that lands somewhere between protest and prayer. When the orderlies arrive—gurney, zipper, the practiced choreography of institutional care—they gently urge him to step aside. Still: “I’m not leaving.” He maintains a single hand on the bedrail as if touch itself were a lifeline, accompanying his father through corridors and into the elevator’s fluorescent hush. Even there, at the threshold between floors and between states of being, he is advised to let the professionals proceed. He does not.

The journey ends in the morgue, that most final of backstage areas. The orderlies slide the body into the freezer with the solemn efficiency of those who perform this rite daily. Sack reaches out for one last contact—an instinctive, human punctuation mark against the blankness of death. The door closes. A beat passes. “And then I left.” In that spare reversal lies the scene’s power. After all the insistence, all the vigil, departure comes in a simple past tense. The line lands not as surrender but as recognition: that love may linger, but the living, at last, must turn back toward the lighted corridors of the world. The effect is haunting precisely because it is so unadorned, allowing the audience to feel the weight of the moment without theatrical cushioning, only the echo of a hand lifted away.

The result at Onassis ONX is a compelling and quietly radiant dispatch from the frontier where theater meets responsive media. It demonstrates, with rare elegance, how technology can function not as garnish but as dramaturgy—light behaving like thought, data carrying the texture of feeling. Sack has already fashioned a mesmerizing hybrid of installation and performance, one whose emotional intelligence matches its technical ingenuity. As the piece continues to evolve, it seems poised only to deepen the resonance it already achieves, perhaps even growing into a title that reflects the singular constellation it has so beautifully begun to chart.

Click HERE for tickets.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on February 6th, 2026. All rights reserved.