and her Children

Directed by Rosie Glen-Lambert With Hailey McAfee and Julia Hoffmann

SoHo Playhouse, 15 Vandam Street, in Manhattan

January 14, 2026 - February 13, 2026

Political iconography, public accountability, and private grief converge with unnerving force in and her Children, the latest offering from The Attic Collective, which comes to SoHo Playhouse’s Fringe Encores with a work of bracing confidence and moral density. This is theater that does not shout its relevance; it simply stands its ground and waits for you to notice how close you are to the blast radius. Anchored by a ferociously controlled, quietly devastating performance from Hailey McAfee, and shaped with exacting restraint by director Rosie Glen-Lambert, and her Children announces itself as a work that is as topical as it is unsettling.

The production takes full advantage of the theater’s intimacy. There is nowhere to hide—least of all for the audience. Over a taut eighty minutes, the play establishes a sustained atmosphere of dread and inevitability, a slow tightening of the vise. Once the piece fixes its gaze on you, it does not blink. The Attic Collective here does more than raise the bar on theater that is ripped from the headlines – it recalibrates the scale entirely.

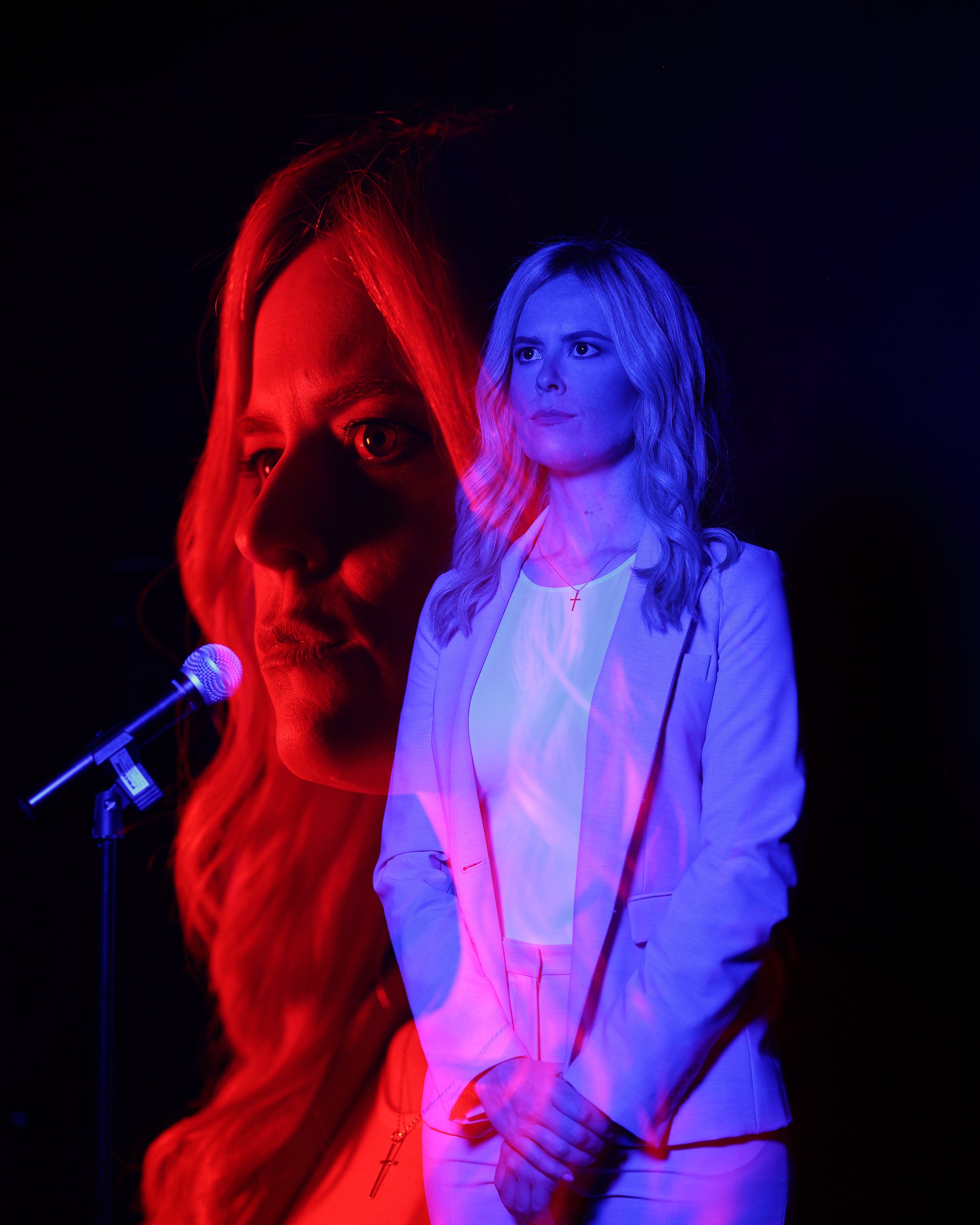

The story opens in a suspended moment—an indeterminate present that feels like a press conference, a reckoning, or perhaps a final rehearsal for absolution. At its center stands Anna Fierling, embodied with chilling poise by McAfee. She enters cool, calm and telegenic, her blonde hair immaculately styled, her posture disciplined, her robin’s-egg-blue power suit punctuated by a gleaming Radiance by Absolute Karoline Leavitt gold cross. She is instantly legible as a professional spokesperson, a woman fluent in sound bites and moral certainty. Modeled in part on NRA firebrand Dana Loesch, Anna has built her career defending not merely firearms but the near-mystical protection of the Second Amendment itself.

McAfee, a performer of remarkable versatility, here achieves something rarer than virtuosity: total authority. From the moment she takes the stage, she commands the room with an ease that feels earned rather than imposed. Her diction is crisp, her timing surgical, her charm disarming. She knows how to silence a space. Yet beneath the polish are hairline fractures—a breath held a moment too long, a smile that falters before being reassembled, a flicker of emotion quickly suppressed. These micro-failures of control are where the play begins to wound. Heartbreak does not arrive with spectacle; it seeps in through the cracks.

As Anna speaks, fragments of her life emerge: a childhood shaped by ambition, a too-early experience of motherhood, a professional ascent from journalist to ideological mouthpiece. The script is careful not to plead her case. Instead, it supplies context, allowing us to see how personal history, institutional power, and political allegiance braid themselves into something dangerously coherent. We are not asked to forgive Anna, but we are compelled to understand how she came to be.

Central to that understanding are her children—Eli, Kat, and Sawyer, modeled after Brecht’s Eilif, Kattrin, and Schweizerkas (Swiss Cheese)—who never appear onstage but are rendered with aching specificity through Anna’s recollections. McAfee animates them with such care that they begin to feel uncannily present: their intelligence, their anxieties, their particular ways of moving through the world. Gradually, their private lives begin to mirror the public catastrophe that frames the play. In their absence, they become its gravitational center, the unspoken weight around which everything else turns.

The narrative discloses itself at a slant, proceeding by implication rather than confession, and steadfastly refusing the satisfactions of easy revelation. Anna speaks directly to us, but never quite to us; her address is calibrated, her voice modulating between serene authority, flashes of sharpened urgency, and the polished cadences of ideological fluency. Each shift in tone feels deliberate, and yet faintly unstable. The audience becomes an unwilling jury, tasked with disentangling what is authentic from what is reflexive, what is belief from what is self-preservation. The play withholds the true dimensions of Anna’s loss until late in its progression, and when that knowledge finally emerges, it arrives without flourish or demand. It lands quietly, devastatingly. The silence that follows is not a theatrical pause engineered for effect, but a collective reckoning—an absence of sound that feels both inevitable and deserved.

What ultimately sets and her Children apart is its rigorous refusal to simplify either its subject or its spectators. Anna is not offered up as a grotesque or a cautionary emblem. She is intelligent, eloquent, persuasive, and deeply implicated—qualities that coexist uneasily, and by design. Most unsettling is her capacity to command our attention and, despite ourselves, our sympathy. One finds oneself admiring her composure, her discipline, her stamina, even as those very traits implicate her in the machinery she serves. The impulse to want her to prevail arrives unbidden, followed almost immediately by revulsion at having felt it at all. That oscillation—between attraction and recoil—is the play’s most incisive achievement. We are not invited to condemn Anna from a safe moral distance. Instead, the work insists that we remain in the tension she embodies, inhabiting the discomfort of contradiction without the consolation of resolution.

Glen-Lambert’s direction is marked by an austere intelligence and an admirable lack of sentimentality. She trusts the material enough to let it breathe, permitting brief flashes of dry humor and glancing moments of levity to emerge organically, without ever loosening the grip of the play’s underlying tension. There is no excess here—no emotional overstatement, no directorial indulgence. Every choice feels calibrated, in service of accumulation rather than release.

Among her most resonant decisions is the inclusion of a live violinist, Julia Hoffmann, seated onstage with bow perpetually at the ready. The instrument becomes a kind of parallel mind, a second consciousness operating just beneath the text. At times the music shadows Anna’s grief, tracing its contours with aching restraint; at others it cuts across her speech, interrupting or reframing it, as if questioning the sufficiency of language itself. In its most potent moments, the violin leads us into an emotional register that words cannot reach, producing an effect that is quietly devastating rather than declaratively tragic—a sonic echo of all that remains unspoken. Anna’s decision to contribute to the musician’s basket may very well be from emotion. Nothing about Anna indicates the gesture would be as perfunctory as dropping a “ten” in the collection plate at church.

The visual design is similarly spare yet loaded with meaning: an American flag, a curtain, a single chair. These elements are less scenery than symbols, arranged with deliberate economy. Lighting does not signal conventional shifts in time or place, but instead marks emotional thresholds, registering internal turns rather than external action. Anna’s carefully constructed appearance—her posture, her grooming, the disciplined coherence of her presentation—functions as an extension of the text. It is a performance within the performance. As the evening progresses, that surface control begins to fray, almost imperceptibly. The costume and makeup design trace this unraveling with remarkable finesse, allowing deterioration to register without ever tipping into exaggeration. This play insists on Anna’s complexity, restraint, and the unsettling humanity that emerges when polish finally begins to crack.

McAfee’s grasp of the character is deep and instinctive, rooted in an acute understanding of how power is both wielded and endured. Control, in her performance, operates simultaneously as armor and as injury—a discipline honed for public survival that has long since calcified into a private burden. She never solicits the audience’s sympathy, never leans into display or emotional excess. There are no histrionic flourishes, no appeals engineered for easy identification. Instead, McAfee holds the line with steely restraint, allowing meaning to accrue through stillness, precision, and the carefully managed suppression of feeling. It is in that refusal to plead or perform vulnerability on cue that the portrayal gains its extraordinary force, revealing a woman whose mastery of composure has become both her greatest strength and her most irreparable damage. Her stillness is a form of dominance. And when that control finally fractures—only to be hastily reassembled, a smile affixed like a shield—the effect is shattering. By the time the play reaches its conclusion, the magnitude of Anna’s loss is unmistakable, and it lingers with physical heaviness.

The statistics are well known. Firearms are now the leading cause of death for children and teenagers in the United States. Hundreds of school shootings. Tens of thousands of young lives shaped by proximity to gun violence. and her Children does not cite these numbers, because it does not need to. They hum beneath the text, part of the ambient noise of contemporary American life. The true horror lies not in this woman losing all three of her children. The horror is in her “survival”; lest we forget, for war reporters, dodging snipers' bullets is all in a day's work.

Click HERE for tickets.

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on January 27th, 2026. All rights reserved.