Anonymous

Written by Nick Thomas; Directed by Sara Fellini

spit&vigor's tiny baby black box theater | 115 MacDougal St #3c, New York, NY 10012

January 31, 2026- February 28, 2026

I love a black box. I love theatre in the round. I love a different theatrical experience. Anonymous gave me all that at spit&vigor’s tiny baby black box theatre. What’s happening here is not immersive theatre in the traditional sense. This is embedded theatre, and the distinction matters. The audience is part of the set but treated like ghosts. The actors can see us but never acknowledge us. There is no interaction, no invitation to participate, and because of that restraint, the experience becomes more intimate, more honest, and far more powerful.

Opening night was a full house, and the room itself does much of the early storytelling.

The year is 1992.

We are seated in the round, about twenty chairs total, close enough to feel each breath and every shift of energy. A radio plays faint strains of 90s music. Coffee is available, oat milk included. The space is a non-descript community center room. Bulletin boards line the walls. Fluorescent lighting hums quietly. A greeter welcomes us and people chat as they settle into their seats. At one point, two audience members nearly break into song. Alright, I was one of the two audience members. I rarely interact with an audience while reviewing, but here it felt organic, spontaneous, and completely aligned with the environment spit&vigor has created.

Anonymous, written by Nick Thomas and directed by Sara Fellini, unfolds during a weekly Tuesday evening meeting of Addicts Anonymous, where six people from different backgrounds gather to talk about their lives. Thomas also appears onstage as Michael, a snooty, rude stockbroker whose sharp edges barely conceal his fragility. Fellini doubles as Elizabeth, a polished socialite whose composure masks deeper unrest, her direction marked by confidence, restraint, and a deep trust in silence.

These are not first-time shares. The stories in the room are familiar, repeated, shaped by time. What we are witnessing is not novelty but ritual. Their regular leader, Charley, is absent. No explanation. That absence immediately shifts the balance. Richard, portrayed by George Walsh, steps in to facilitate. Walsh’s Richard is kind, caring, and quietly grounded. It is his creation of a safe space that allows truth to surface. His leadership invites risk, not through control, but through steadiness. The explosive moments that follow do not exist in isolation. They open doors for others to go there too. His nervousness, paired with an earnest desire to do right by the group, is beautifully embodied, making his authority feel earned rather than assumed.

This is where the embedded nature of the production truly shines. We sit among them, listening. Watching. Knowing things before they are spoken. We are present but silent, all-seeing voyeurs inside a room built on trust, routine, and unspoken rules.

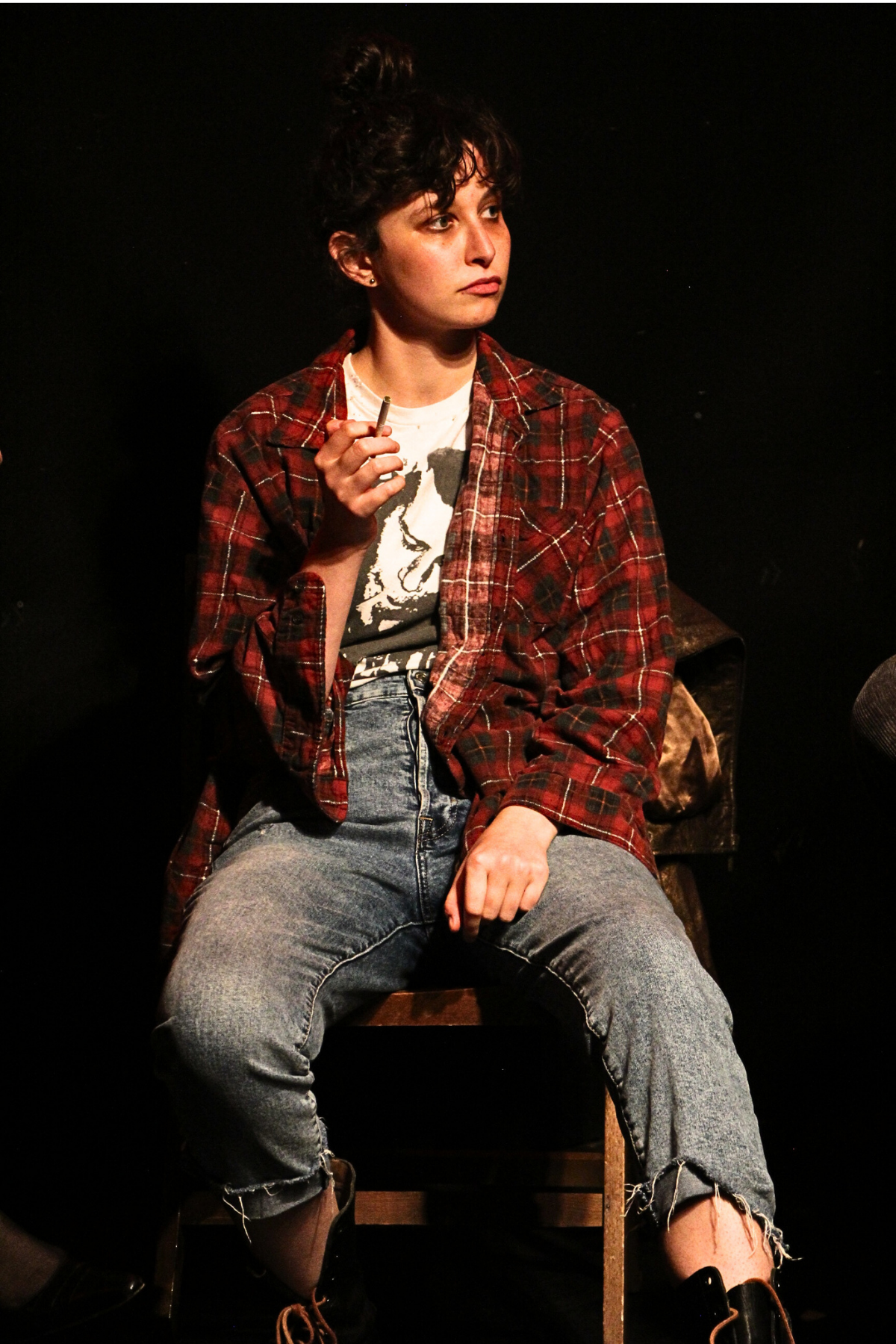

Daliah Bernstein plays Sarah, a woman navigating sobriety while still working at a bar and pursuing life as an actress and model. The tension between her environment and her recovery is ever-present, and Bernstein captures it with clarity and strength. Steven Gamble is Blake, an ambulance driver who saves lives every day, or so we are led to believe. His performance subtly interrogates hero narratives and the emotional armor people build when they are constantly expected to be dependable. Azumi Tsutsui delivers a stunning performance as Diana, a quiet explosion that brings the audience to a standstill. Her restraint is magnetic. When she finally breaks through, the moment is volatile, raw, and deeply earned, shifting the emotional gravity of the room.

The stakes escalate with the sudden return of Charley, portrayed by Jesse James Metz. Metz’s Charley is not a villain. He is unraveling. His return disrupts the fragile progress the group has made and reminds us not to idol worship or place people on pedestals. People are human. Leaders are human. That humanity can be both grounding and destabilizing.

Set in 1992, the play operates in a world without smartphones, social media, or the internet. Information moved through radios, televisions, newspapers, and word of mouth. Conversations like these happened in therapy rooms, doctors’ offices, and closed meetings, if they happened at all. For many of us who came of age in the early 90s, the cultural norm was silence. You didn’t talk about your problems. You pushed forward. Or you drank. Or you found some other destructive coping mechanism. That context matters. This play is not nostalgic. It is observational. It reminds us that trauma did not begin once we had the language to name it. What Spit&Vigor captures with unsettling accuracy is the weight of that silence and the fragile courage required to break it.

This production forces each character to confront their own truth and decide what healing actually looks like. Not everyone gets it right. That’s the point. You leave reminded that everyone has a story. Sometimes even they do not fully know what it is yet. And sometimes, sitting in the room and listening is the bravest thing anyone can do.

Click HERE for tickets.

Review by Malini Singh McDonald.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on January 31th, 2026. All rights reserved.