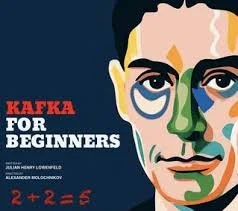

Kafka for Beginners

Written by Julian Henry Lowenfeld; Music composed by Julian Henry Lowenfeld

59 E 59 Theatres | 59 East 59th Street, NY, NY

July 22 - July 26, 2025

Julian Henry Lowenfeld’s Kafka for Beginners is a fiercely stylized descent into the machinery of state-sanctioned madness. This is no mere play, but a fevered cry from the belly of an empire rotten with its own myth-making. Here, power has calcified into ritual, and truth is a currency long outlawed, hence we have declarations like “Everything not forbidden is compulsory!!! Everything not compulsory is forbidden!!! 2 + 2 = 5!!!” Further gems such as “In related scientific news, The Imperial Ministry for the Enlightenment of the Folk announced that the body of water formerly known as the Pacific must now be called the Heroic Ocean,” could have started a press briefing from the desk of Karoline Leavitt and we no longer need to blink.

Though ostensibly confined to a single act, the play unfolds with an ambitious temporal sweep, spanning not merely days or months, but a series of unsettling, fractured years. This narrative distension—subtle yet deliberate—imbues the production with a kind of temporal vertigo, a disorienting sense that time itself is a character: capricious, unkind, and tragically cyclical.

The entirety of the drama is staged in and around that most chilling of institutional constructs: a “penal isolator,” a euphemism so sterile it only magnifies the terror of what it conceals. It is, in essence, a punishment cell—bleak, unrelenting, and all too familiar in its architecture of control. This claustrophobic setting is overseen by the shadowy bureaucrats of the so-called Imperial Ministry of Redemption, a name so drenched in irony that one hears it with an audible sneer. It is the ruling arm of the Ozymandian Empire, a regime whose very title evokes fallen grandeur and tyrannical decay—a not-so-distant echo of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ruined king.

And herein lies the most chilling stroke of the playwright’s vision: the time, though unnamed, seems to press against our own with unnerving intimacy. It is not set in some remote dystopian future, nor safely anchored in the annals of a distant past. No, the time is disturbingly proximate—achingly similar to our present moment. The atmosphere is saturated with contemporary dread, with the kind of moral disintegration and bureaucratic violence that does not belong only to fiction. The play, in this sense, becomes a mirror held aloft—though it reflects not only our faces, but the prisons we build around our consciences.

In short, this is a play that dares to compress years of anguish into a single, unblinking act, and places us squarely inside a system that feels as though it could exist just beyond the walls of the theatre—or perhaps within our own.

Within this joyless dominion — a place where the very anthem of the land proclaims with unblinking certainty that 2 + 2 = 5 — we meet our protagonist, known simply as The Poet. And what a tragic figure he is: both Cassandra and Prometheus, damned not for what he says, but for what he knows and dares to believe in silence. His great offense? Not shouting defiance from rooftops, but quietly refusing to swallow the lie.

When the regime’s chillingly named Ministry of Redemption — a grotesque parody of salvation, as only Kafka could have imagined — infiltrates his digital sanctum and discovers this private heresy, he is swiftly and remorselessly “disappeared.” Thrown into a nameless, featureless cell somewhere at the frayed edge of civilization, the Poet is subjected to an exquisite program of psychological erosion and corporeal torment. Think Orwell meets Artaud — with a dash of Brechtian distance to keep you wincing with intellectual clarity even as your stomach turns.

And yet, amid this bleak theater of pain and propaganda, the play never loses its grip on the central moral dilemma: Is there a point at which truth itself becomes unspeakable — or even expendable? The Poet’s captors do not merely seek compliance; they seek conversion. They offer him liberty — but only the liberty of the broken, the reprogrammed, the complicit: “This is your chance, sir! You just have to speak some words you don’t really believe to some folks who don’t really care, and you’re done!...Just think of your wife and kids, sir, just look into the camera, smile, and say: “Two plus two is five.” Then you’ll be free!” to which our Poet replies, “No, if I do that, then I will not be free! I’m freer in here, where I don’t have to lie.”

Agent 9 and the Supervisor have their jobs to do, and so do the roaches that crawl over the Poet during the night and the Spider who has webbed himself into a corner, a creature the Poet has named Walt after the poet Walt Whitman who he frequently quotes as a reference point.

Thus, the narrative coils itself ever tighter around a single, harrowing question: Will the Poet renounce his truth to gain his freedom, or will he cling to what he knows and be destroyed?

Covid seems to be on the attack again in 2025 and this reviewer’s performance was affected by the lead actor bowing out due to illness. Actor Kane Parker who normally plays Agent 9, and sympathetically at that, rose to the occasion and performed the yeoman’s service of performing the role of the Poet as well, albeit with a script in hand and physically repositioning himself on stage for the change in character speaking as the text required. Thankfully Mr. Parker’s performance, and Mr. Lowenfeld’s play, were no worse for wear in what must have been a very challenging rehearsal to walk through before the audience arrived. Kudos to Mr. Parker and perhaps he may one day inherit the role of the Poet and do justice to that as well.

Kafka for Beginners is no light fare. It is a theatrical gauntlet — a dark parable that forces the audience to confront the ease with which reality can be rewritten, and the excruciating cost of saying no when the world demands yes. The pity lies in, or rather the crystal ball nature of the piece lies in this work being less the intended satire and more, unfortunately for Americans, a ripped-from-the-headlines reality.

Kafka for Beginners played its last NYC/ East to Edinburgh performance on July 26.

Performances continue in the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, now through August 24.

Venue: Alba Theatre at Braw Venues @ Hill Street, 19 Hill St EH2 3JP

To book Edinburgh Fringe tickets, https://www.edfringe.com/

Review by Tony Marinelli.

Published by Theatre Beyond Broadway on August 7, 2025. All rights reserved.